Evaluation-Driven Development

Intelligence is a Cost, Not a Virtue

I frequently speak with teams at large companies where the mandate comes from the top. The boss tried ChatGPT, found it intuitive, and now expects an autonomous agent that solves complex workflows. The technical team has been trying it for months, the reliability is poor - even if the accuracy is acceptable (which is rarely seems to be), it fails spectacularly on important edge cases.

Worst of all, companies rarely seem to have a rigorous benchmark to test against because stakeholders are often uninterested in the tedious work of creating evaluation datasets - they often make a half-hearted effort to provide enough feedback and test cases.

I saw this general scenario play out at PyData London 2025, one of the best conferences for data science (and in extension ML and AI) in Europe. Speaker after speaker presented slides explaining LLM capabilities with cherry-picked examples. Then came the final slide admission: they weren’t sure it worked on all their data, it was too slow, and the cost was prohibitive.

Testing LLM-based processes more often than not represents a shift from rigorous engineering to vibe-based coding. Engineers check a prompt in a chat interface to verify it works. They tweak it a few times, and yeah, it seems right. This manual check provides false confidence. A prompt working today with specific temperature settings might fail tomorrow.

Testing LLM-based application is difficult, let’s face it. Traditional testing relies on strict assertions where f(x) must equal y, but this collapses when y is not a single value but a probability distribution. In stochastic systems like LLMs, identical inputs can produce many valid outputs, making literal string comparisons brittle and generating flaky tests that fail even when behaviour is correct. Because LLM tasks rarely have a uniquely correct answer, strict equality penalises harmless variations in phrasing, ordering, formatting, or reasoning style.

This noise only grows with sampling variance and model updates, causing developers to lose trust in the test suite as false negatives drown out real regressions. Even the notion of a perfect ground truth breaks down, since many tasks allow multiple acceptable interpretations, and annotations themselves can be uncertain or incomplete. As a result, correctness for LLM systems is better defined not by matching a single exemplar, but by satisfying semantic, structural, and behavioural constraints across a distribution of outputs, evaluated through similarity metrics, schema checks, probabilistic thresholds, and robustness criteria rather than literal matches.

Without quantitative baselines, developers play a game of Regression Roulette. They optimise for a single trait like tone and silently degrade factual accuracy. They trade one error for another. Development velocity slows because the team fears that fixing one prompt will break another workflow.

Engineers rush to the most complex tool before defining success. And executive demand it to get the board behind them. Most AI projects fail for a simple reason: teams jump straight to the most complicated and expensive solution before defining what success actually looks like. That creates runaway costs, unpredictable output, and no measurable progress.

The Economics of Simplicity

The economic implications are increasingly impossible to ignore. In many practical workloads, an embedding-based classifier delivers similar or even superior accuracy to a GPT-4-level model at a tiny fraction of the cost, and this is talking about solutions that are up to 90 times cheaper per request, without sacrificing measurable performance. That cost delta becomes enormous at scale: what costs tens of thousands of dollars per month with generative models can drop to a few hundred dollars with embedding search. In economics, this is called structural margin expansion.

Speed amplifies the gap further. Faster responses don’t just improve UX, they directly increase conversion, retention, and user trust. A keyword or rule-based match resolves in under a millisecond. An embedding search returns in under a hundred. Meanwhile, a multi-step agentic workflow with an LLM operates on the scale of seconds, and users rarely tolerate that delay unless absolutely necessary. For most tasks, the latency itself becomes an economic loss: fewer completed actions, abandoned flows, and higher infrastructure costs to maintain concurrency.

This is why the question executives and engineers alike must ask is no longer “Can an LLM do this?” because the answer is almost always yes, maybe. The real question is:

“Do we actually need an LLM to do this?”

And nine times out of ten, the data says no.

Evaluation-Driven Development

We need to invert this development process with something that I’d like to call Evaluation-Driven Development. Projects often start with a vague mandate to use AI rather than a concrete business problem. But generic tools rarely adapt to domain knowledge, enterprise data pipelines, or compliance requirements.

The philosophy is simple: metrics first, tools second, and complexity last (Evaluation-First, Complexity-Last). Intelligence (especially generative inference) is an expensive resource, both in terms of latency and money, and should be treated as a cost rather than a virtue. We must stop asking if an LLM can do a task and start asking if we need one to do it.

Definition: Evaluation-Driven Development

A disciplined methodology for building AI systems that prioritises measurable outcomes, starts with the simplest sufficient method, and escalates complexity only when empirical metrics demand it.

EDD replaces the traditional Red-Green-Refactor cycle with a new loop adapted for probabilistic systems - Measure-Optimise-Monitor:

Measure (“Red”): Before writing a single prompt, define your “North Star” metrics (e.g., Latency < 200ms, Faithfulness > 0.9) and curate a Golden Dataset of inputs and expected outputs. Establish a quantitative baseline to drive development.

Optimise (“Green”): Iterate on your architecture to hit your metric thresholds. Treat prompts as optimization parameters.

Monitor (“Refactor”): Deploy evaluation pipelines to production to continuously score live interactions and detect drift, hallucination, or degradation over time.

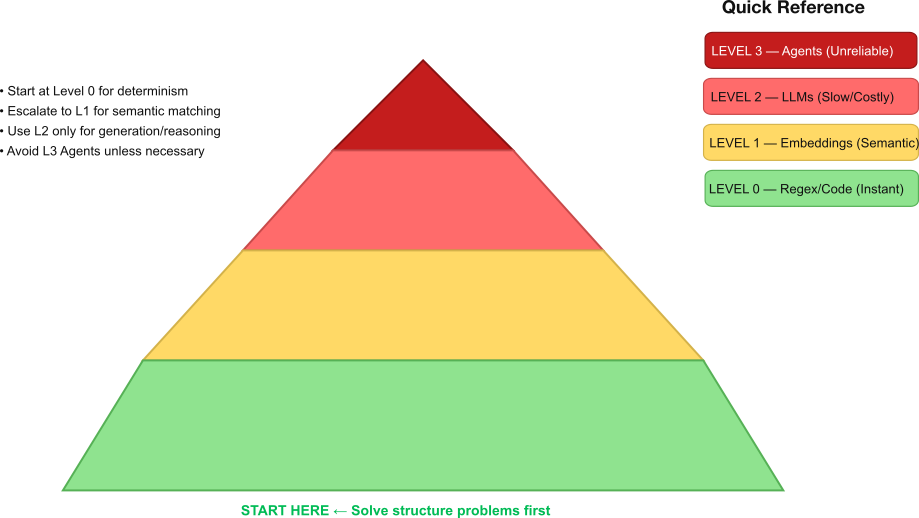

The Complexity Pyramid

We visualise our architecture as a pyramid. The goal is to solve problems at the lowest possible level before escalating.

Level 0: Heuristics (“The Rule Book”) At the base of the pyramid are heuristics: regex, keyword matching, and explicit code logic. These are deterministic, free, and execute in microseconds. Despite the hype surrounding LLMs, a significant portion of user queries (like “reset password” or order tracking) are structured enough to be handled here.

When to Use It: You need speed above all else, the problem has predictable patterns, or you want to filter obvious noise before it reaches expensive models.

Level 1: Embeddings (“The Semantic Compass”) Level 2 introduces semantic understanding without the overhead of generation. By using vector search and cosine similarity, we can classify intent, handle multi-lingual inputs, and perform fuzzy matching for fractions of a cent per query. This level measures the mathematical distance between concepts, understanding synonyms and related ideas without training specific data.

When to Use It: Keywords fail due to synonyms, you need to classify text broadly (e.g., “refund” vs. “support”), or you require accuracy better than simple rules but cheaper than an LLM.

Level 2: LLMs (“The Generative Engine”) This is the domain of Large Language Models. In an EDD architecture, we view these as “reasoning engines” of last resort. They are powerful but probabilistic, meaning their output varies and they are prone to hallucination. This level is capable of complex synthesis and transformation, but with high latency and operational cost.

When to Use It: The task requires generative creativity, complex reasoning over unstructured data, or you can afford the high cost and slower speed for a specific, high-value interaction.

Level 3: Agents (The Probabilistic Layer) Finally, autonomous agents sit at the top. This is the highest risk layer where errors accumulate. In a multi-step workflow, a 90% success rate per step degrades to near coin-flip reliability (approx. 53%) after just six actions. This layer should be reserved for novel tasks requiring tool use where human supervision is available or failure is acceptable.

Complexity Escalation

The methodology is straightforward:

Start by defining the evaluation dataset, the concrete examples that represent success. Only once success is measurable do we build. Then, implement the simplest possible abstraction that achieves the required metric. If a rule meets 95%, use the rule. If the rule fails, try embeddings. Only escalate to a generative model when the lower layers fail and the metric justifies the added cost, latency, and risk. In other words, complexity must be earned, not assumed.

This discipline produces more than just cheaper systems, it produces better systems. Systems that are deterministic enough to audit, efficient enough to operate profitably, and reliable enough to scale without hidden failure modes.

At Chelsea AI Ventures, a London-based AI development consultancy, we focus on strong engineering practices for implementing bespoke AI systems.